Capturing the Life of the Yucatán Jungle: Documenting a Biodiversity Baseline

July 01, 2025

Project Updates

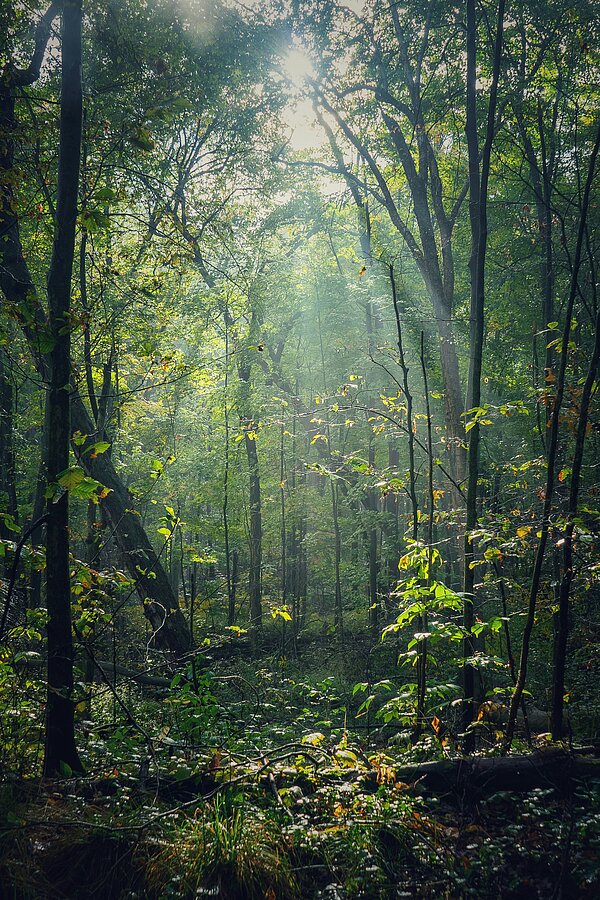

Dawn breaks in the tropical forests of Quintana Roo, Mexico. A chorus of bird calls echoes through the canopy as shafts of sunlight pierce the mist. We at FORLIANCE step carefully along an old Maya footpath, guided by dew-covered tracks on the forest floor. This morning, our team isn’t alone – hidden “eyes” and “ears” we placed weeks ago have been watching and listening. Today, we retrieve those camera traps and acoustic recorders with anticipation, knowing they hold precious glimpses of wildlife that roam when humans aren’t around. It’s the culmination of our 2023 biodiversity baseline survey in the XiCO₂e: Mexican Peninsula Forest Project, a community-driven conservation effort we lead in the Yucatán Peninsula.

Setting the Stage: A Forest of Global Importance

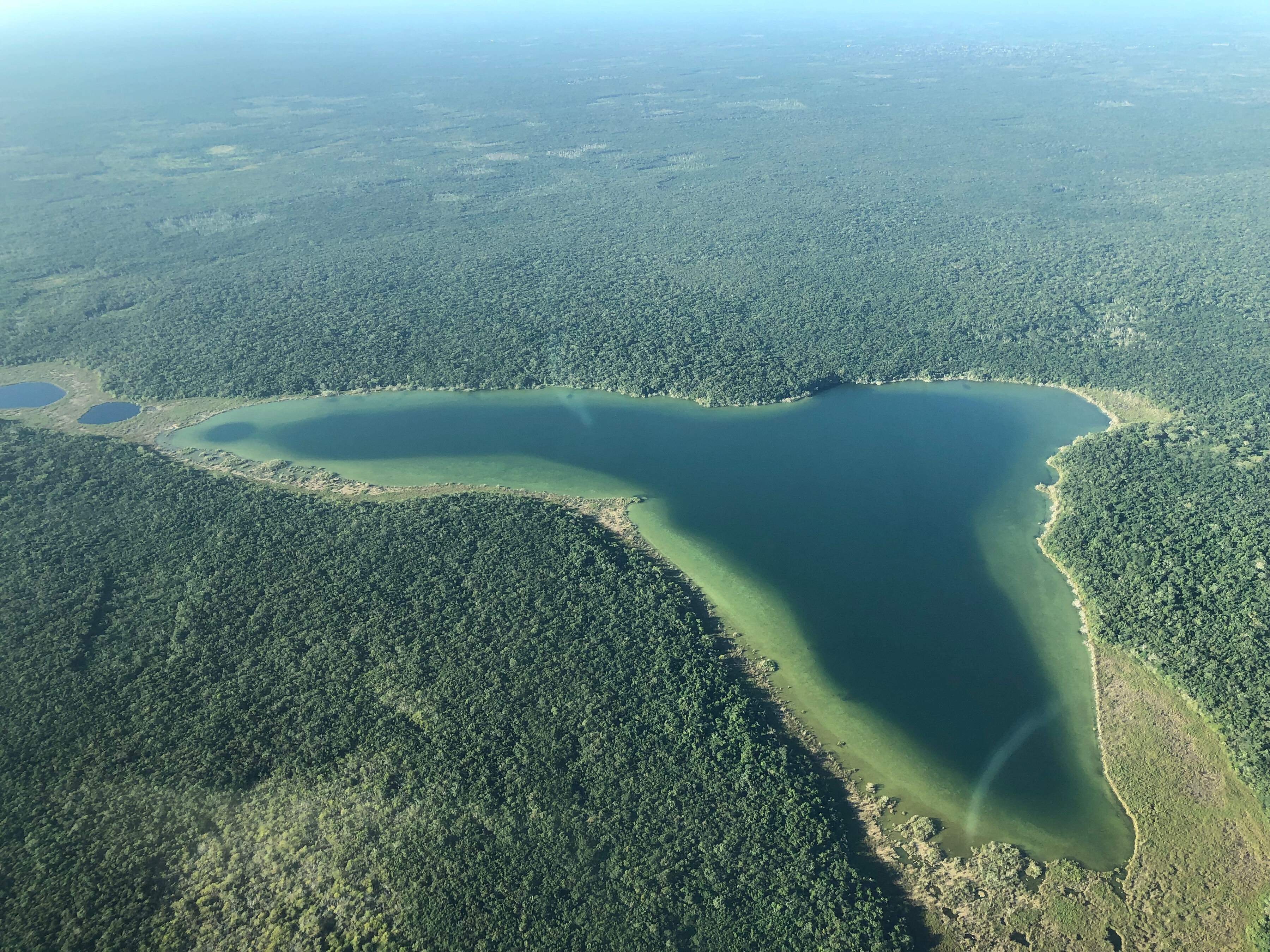

Nestled in southeastern Mexico, the XiCO₂e project spans roughly 37,000 hectares of tropical forest in Quintana Roo. This landscape is part of the Yucatán Peninsula’s emerald expanses – Mexico’s largest remaining stretch of tropical rainforest. It forms the heart of the Selva Maya, a transboundary wilderness shared with Guatemala and Belize, renowned globally for its ecological significance. Hundreds of species of birds and mammals live here, including endangered icons like the Baird’s tapir and elusive big cats. In fact, this forest is one of the few places left that can sustain a viable jaguar population. Every inch of this land brims with life: vibrant toucans and parrots flit above, while keystone species like jaguars, pumas, and white-lipped peccaries quietly pad below the dense canopy. There are even hidden waterways that harbor creatures such as crocodiles and, in nearby wetlands, the West Indian manatee. Simply put, our project area is a vital sanctuary of biodiversity on a global scale.

But this rich forest has long been under pressure. Agricultural expansion, unsustainable logging, and new infrastructure have been nibbling at its edges. Many local communities (ejidos) remember when illegal logging was rampant and wildlife seemed to dwindle. That’s why FORLIANCE partnered with local organization Ala boOl and the ejidos to launch the XiCO₂e project – to promote sustainable forest management and protect this irreplaceable ecosystem. From the outset, biodiversity was not a side benefit; it was a core pillar of the project’s design. While the initiative indeed aims to sequester carbon and mitigate climate change, we made it clear that saving the forest’s wildlife and plant diversity is just as fundamental as capturing CO₂. As project lead, we at FORLIANCE are committed to science-based conservation that strengthens local livelihoods. Community-led forest stewardship, regular training in sustainable practices, and constant ecological monitoring are all part of the plan. In 2023, to turn our commitments into action, we embarked on a comprehensive biodiversity baseline survey – essentially, a “wildlife census” to document what lives in these forests today. This baseline will guide us for decades to come.

Eyes and Ears of the Forest: Tools of Discovery

Conducting a wildlife survey in such a vast, dense jungle is no small feat. Our biodiversity team – led by field biologists Edith Berenice Espinosa García and Aida Medina Agustín – spent weeks deep in the field for this baseline. Together with community members trained as para-biologists, they set up an array of camera traps and acoustic monitors to become the “eyes and ears” of the forest day and night. Camera traps are motion-activated cameras strapped to trees, and they silently snap photos of any creature that walks by. These gadgets allowed us to observe elusive, mostly nocturnal animals without disturbing them. “These camera traps are like our hidden allies – working 24/7 so we can peek into wildlife’s secret life,” says Edith, who has spent over a decade studying Yucatán’s fauna. The cameras were carefully placed near animal trails, water sources, and fruiting trees – spots our local guides suspected were wildlife hot spots. Each camera trap, equipped with infrared sensors, captures images even in the pitch dark, giving us a window into the forest’s nightlife.

Meanwhile, passive acoustic recorders were installed in various locations to capture the soundscape. Many forest animals reveal themselves by sound – the territorial calls of birds at dawn, the dusk chorus of insects and frogs, even the distant roar of a howler monkey. Modern acoustic sensors can record wildlife sounds for weeks, storing audio data that ecologists later analyze for distinct species calls. “At sunset we’d hear an orchestra – frogs croaking, insects buzzing, owls hooting,” Aida recalls. “The acoustic monitors let us save those moments and identify who is present even when we can’t see them.” Using audio spectrogram software, the team can pick out unique signatures – a toucan’s croak or a bat’s ultrasonic chirp – and thus confirm the presence of species that are otherwise hard to spot. This technology, Aida explains, is particularly useful for monitoring birds and amphibians. It’s also non-invasive and efficient, covering many species at once just by listening. In tandem, the camera traps and acoustic devices paint a comprehensive picture of the biodiversity hidden in these woods.

Setting up camera traps together with the local communities.

The Human Touch: Communities Leading the Way

Central to this entire effort is the local community. The XiCO₂e project is built on the principle that conservation works best when it’s driven by those who know the land intimately. In Quintana Roo, that means the indigenous Maya ejidos who have managed these forests for generations. From day one, local elders, ex-hunters, and youth volunteers were involved in planning the biodiversity survey. Their knowledge – of animal tracks, fruiting seasons, watering holes – proved invaluable. “I remember a village elder pointed at some scratch marks on a tree and said, ‘Jaguar was here,’” Edith recounts with a smile. “Sure enough, our camera later confirmed a big male jaguar patrolled that very spot.” We learned countless such insights from community members: which trees the toucans favor, how the wind direction at night can carry monkey calls, or how certain frog species appear after heavy rains. Biodiversity conservation is most effective when all stakeholders are involved – especially local land stewards. Seeing former hunters now passionately protecting wildlife was one of the most inspiring outcomes of this project. As Aida puts it, “The forest is their home. Their fathers and grandfathers taught them its secrets. Working side by side with them, we combined science with tradition – a powerful combination.”

The fieldwork often turned into an impromptu exchange of knowledge. During daytime transect walks (systematic hikes through the forest), ejidatarios pointed out medicinal plants and animal burrows that our scientists might have missed. In turn, our team explained how the camera trap images would help establish a wildlife inventory and why that’s key for long-term protection. The collaboration built trust and pride. Community members took ownership of the process – they helped choose camera sites, maintained equipment, and eagerly waited for the results. In the evenings, everyone would gather around a laptop in the village community center to review any new photos or audio recordings. The excitement was palpable when villagers recognized a creature from a photo – “Mira, un tepezcuinte!” (Look, an agouti!) someone would shout, or “We heard a saraguato (howler monkey) near the river, it’s recorded here!” Through these moments, science became something inclusive and empowering. This isn’t a project done to the community; it’s led by the community with our guidance. We at FORLIANCE firmly believe that protecting nature goes hand in hand with supporting people – and in XiCO₂e, that bond has only grown stronger.

Wildlife Encounters: Capturing Nature’s Stories

After many weeks in the field, the biodiversity baseline survey revealed a treasure trove of wildlife. When Edith and Aida’s team finally collected all the camera trap memory cards and audio files, they could hardly contain their excitement. Back in the camp laboratory – a simple hut with a generator and laptops – they clicked through image after image like children unwrapping gifts. There it was – a jaguar! In one nighttime photograph, a muscular jaguar with rosette spots pads silently past the lens, eyes glowing in the dark. In another, a puma (mountain lion) slinks through dappled moonlight, a ghost in the night. “It’s one thing to know these big cats roam here, but seeing them with our own eyes – even if just in a photo – was thrilling and humbling,” Edith says. For her, that jaguar photo was a career highlight. Jaguars are an umbrella species; if they are thriving, it means the ecosystem is healthy enough to support large prey and wide territories. Knowing that at least one jaguar confidently walks these forests at night underscored the importance of everything the project is working to protect.

And the highlights kept coming. A series of shots showed a Baird’s tapir – a rare, pig-like herbivore – snuffling through the underbrush with its prehensile snout, likely unaware of the camera documenting its midnight snack. Other images captured white-tailed deer and peccaries foraging, armadillos and anteaters trundling by, and even curious ocelots and margays (smaller spotted cats) investigating the camera with bright, reflective eyes. Daytime photos unveiled the daytime caretakers of the forest: troops of Yucatán black howler monkeys high in the branches, gangs of coatis nosing the ground, and brilliantly colored birds. One camera trap near a fruiting fig tree treated us to a parade of toucans and parrots. Their vibrant plumage stood out even in still images – keel-billed toucans with their rainbow bills, red-lored and white-fronted parrots jostling for a meal. In the acoustic recordings, our ornithologists later identified dozens of bird calls, including the distant croak of the scarlet macaw – a species once endangered in the region, now slowly recovering. Hearing the raucous call of a macaw and the haunting hoots of owls on the soundtracks gave us goosebumps; it was like the forest speaking its own language. Every photo and every soundbite was a reassurance that this forest is alive and well.

There were also reptile and amphibian encounters. While snakes and lizards are harder to catch on camera, we found signs of their presence: shed snake skins on the trail and the acoustic monitors picked up the nighttime chorus of tree frogs and toads. One daylight video clip even caught a turquoise-browed motmot swooping down to snatch an unsuspecting lizard – a small drama of predator and prey. “Moments like that remind us how every creature here, big or small, plays a role,” Aida notes. Some of the species documented are endemic – found nowhere else on Earth except this corner of Mesoamerica. For instance, we photographed the ocellated turkey, a dazzling turkey species native to the Yucatán, and recorded calls of the Yucatán jay, a vivid blue-black bird unique to the region. Each finding, from the tiniest frog to the mightiest jaguar, was carefully logged. By the end, we had compiled a baseline inventory listing dozens of mammals, hundreds of birds, plus countless reptiles, amphibians, and insects. This baseline confirms that the XiCO₂e project area is a haven of biodiversity, echoing what scientists have noted about the broader Selva Maya region. It’s rare in our world today to see such intact richness – and it strengthened our resolve to keep it that way.

From Baseline to Legacy

With the 2023 biodiversity baseline complete, our work is far from over – in fact, it’s just beginning. This survey is the starting point for long-term biodiversity monitoring in the XiCO₂e project. By establishing baseline data on species presence and abundance, we now have a yardstick against which future changes can be measured. We plan to conduct follow-up surveys regularly in the coming years, involving even more community members and incorporating new technologies as they become available. “This baseline is like a first chapter in a book,” Edith explains. “Every few years, we’ll write new chapters through monitoring, and together they’ll tell the story of how our conservation efforts are making a difference – or where we need to adapt.” Adaptive forest management is a key principle here: if the data show certain species declining or new threats emerging, we will adjust our strategies. For example, if acoustic monitors indicate fewer bird songs over time, we might investigate and enhance habitat for those birds. If camera traps show an uptick in poaching or encroachment, the community patrols can be increased. In this way, the baseline and ongoing monitoring form a feedback loop, ensuring that forest management is guided by science and real-world observations.

Crucially, the baseline also helps quantify the co-benefits of this climate project. Carbon capture can be measured in tonnes, but how do you measure life? By documenting wildlife now, we can later demonstrate how protecting the forest for carbon also protects biodiversity – proving that climate action and nature conservation go hand in hand. Forliance’s approach has always been holistic: climate, community, and biodiversity benefits are intertwined. We’re proud that XiCO₂e’s climate project is as much about jaguars and macaws as it is about carbon reservoirs. The results from 2023 have already been heartening. They show that the ejidos’ forests are teeming with life, and that community vigilance (supported by our project) has likely helped deter illegal logging and hunting in recent years. As one local community member told us during a celebratory meeting, “Antes, casi no veíamos animales grandes. Ahora, regresaron” – “Before, we hardly saw big animals. Now, they have returned.”

We at FORLIANCE feel privileged to support and lead this effort. The XiCO₂e Mexican Peninsula Forest Project is a testament to what community-driven, science-based conservation can achieve. Biodiversity is the foundation of this project’s success, not an afterthought. By safeguarding the jaguars’ roamings and the birds’ songs, we are also safeguarding the environmental services – from pollination to water regulation – that keep local communities thriving. And the story resonates far beyond Quintana Roo. In a world where forests are often seen only as carbon stocks, XiCO₂e is showing a different path: one where people, climate, and wildlife all thrive together. As we pack up our field gear and the jungle settles back into its daily rhythm, we carry with us a deep sense of responsibility and optimism. This baseline survey is the first step in a hundred-year journey (the project’s duration) of caring for this forest. We have many more camera traps to check, many more sounds to hear, and many more memories to make with the communities and creatures of the Yucatán Peninsula. The forest’s story is still being written, but one thing is clear – its future is brighter because a committed team of locals and conservationists have joined forces to protect it, for the benefit of all of us and generations to come.